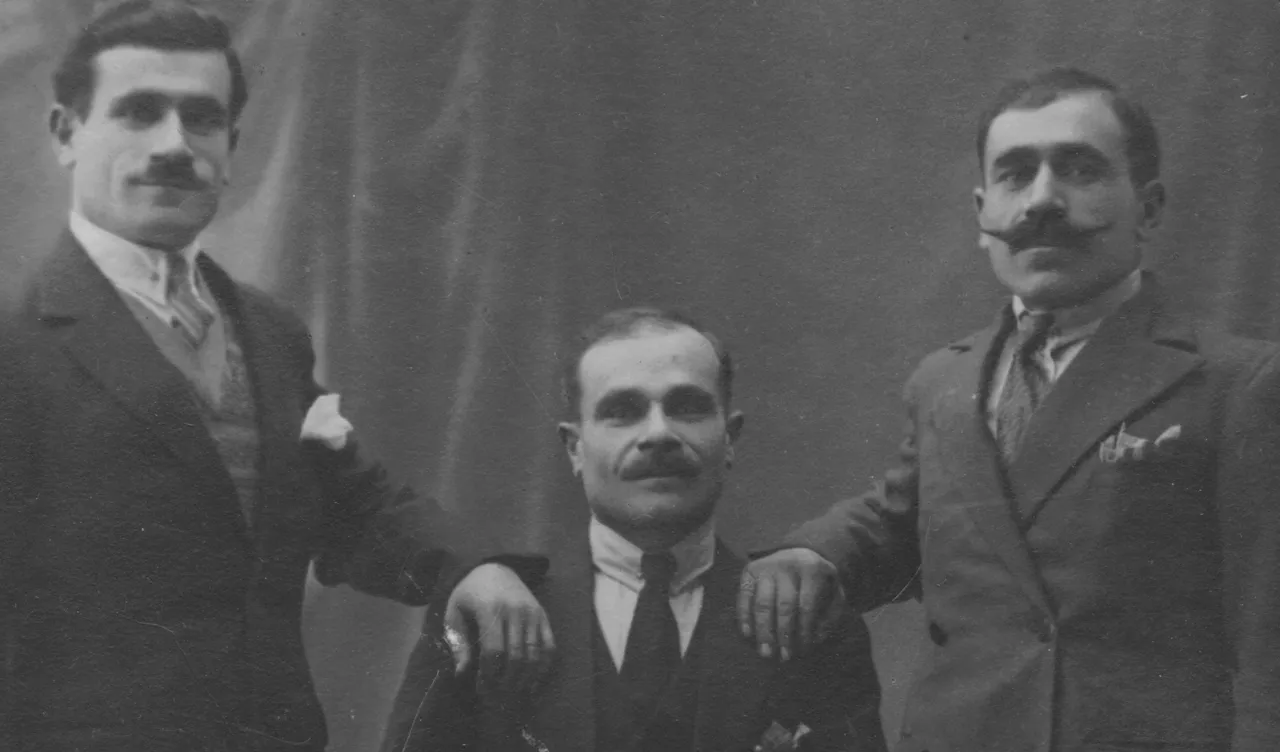

The story of Arakel Bahaderian (Center of the photo)

written by Krigor Bahaderian (His son and my grandfather)

Before delving into the main subject, it is good to remember the premises from which this event began. My father's family were among the oldest residents of Hajin city in Turkey, who immigrated from the Caucasus, more precisely from Artsakh, according to historical facts.

My father used to say that their family had six sons, and their father managed to feed them all with his only donkey, with which he transported loads left and right. One day, my father's brother asked to borrow the donkey for a day to transport a load, and of course, my grandfather did not refuse and received the unexpected result. My grandfather's brother loaded so much on the donkey that the poor creature died, and the two brothers quarreled forever. During his childhood, my father attended a local Armenian school and later learned weaving. The large size of the family forced him to move to other cities in search of work, as was done at that time to feed the family and solve social issues.

Today, the same thing happens in Armenia, where many families go abroad in search of work to survive, sometimes ending in tragedy.

Such was the case with my paternal uncles in 1909 when they were in Adana. In April 1909, when the government of the Young Turks organized the massacre of Armenians, my three uncles were killed. When the Turks attacked Armenian neighborhoods, my uncles hid in wine and wheat jugs, but their hiding place was betrayed by an Armenian. The Adana massacre still amazes us today with its occurrence, and in general, with the Turkish governments' mindset of why they slaughtered the working people who always created goodness, prosperity, and development for the country.

In my opinion, the Turks were not acting independently, but under the influence of foreign diplomats, who wanted to see a sickly, bedridden Turkey, which would be easier to divide. Let's leave the conclusion to experienced diplomats and continue with our family story.

The death of my uncles was a great blow to our family, but there was no other way; life had to continue. My great uncle, Ghazar, was engaged to a girl from the Petenyans before going to Adana, and since a new family was starting between the two families, my father married his brother Ghazar's fiancée.

Two boys were born from the marriage, named Tigran and Manuk.

In 1915, emigration began. My father's family was not spared from this catastrophe either and was exiled to Syria. On the way, the parents died, and my father reached the city of Hama with his wife and two children, from where they went to one of the villages of Hama and stayed until 1918. In that village, my father established a weaving workshop and began to work. The craft proved beneficial, and my father was able to feed the family and return to Hajin in 1918 with some money after the signing of the peace treaty. (Details can be known from possible pages of history.)

Upon returning to Hajin in 1918, life resumed, and people began to repair the houses abandoned four years earlier, renovate the gardens, restore the economy, and gradually get back to normal.

History tells us that the Kemalist movement had started in Turkey. The financiers of this movement were the newly created Bolshevik Russia (with Lenin’s intervention), France, England, and Italy, all of which had one goal (let's not deviate from our main topic).

The Kemalist movement aimed to completely annihilate Armenian communities, including Hajin. Initially, Turkish raids on Hajin were small-scale, and they failed to capture the city through blockade means. The Hajin residents managed to repel the Turks' attacks.

Historian Gerard Chaliand describes the details of Hajin's defense quite well in his book (incidentally, Gerard Chaliand is the nephew of the mayor of Hajin).

In 1920, the great siege of Hajin began and lasted until October 15, 1920. At the beginning of 1920, Hajin city started preparing for resistance. The Turks' small artillery, placed on a hill opposite the city, sometimes disturbed our residents, so the Hajin residents decided to capture the cannon. My uncle Simon, who was only 17 years old, also participated in this attack. The Hajin residents managed to attack at night and isolate the artillerymen. Here, the Hajin residents made a mistake; they dropped the cannon into a valley and went a month later to retrieve the cannon with its shells and bring them to the city.

After these failures, during the summer months, the Turks contented themselves with smaller attacks that did not greatly disturb the Hajin residents. Mayor Karapet Chaliand called the city council in those days and proposed to leave the city and, with the help of armed citizens, move ahead with the cannon and take the Adana route. The proposal was not accepted by the hot-tempered youth who believed they were invincible.

There were also other reasons. The main commander of the defenders, Sargis Chapedjian, was injured in the thigh and it was difficult for him to travel that long road. The second part of the youth did not want to leave their ancestral homes and properties. (This mistake became fatal for the unarmed population; all were massacred on the night of October 15 to 16.) My father's cousin, Avag Ghazaryan, dressed in contemporary disguise, like a Chète (as Turkish fighters were called), with four friends, sought ‘Gavours’ when Turks called Armenians. But Avag's aim was to find any Armenians who survived the massacre, which he did not succeed in, as it turned out that the Turkish forces ruthlessly slaughtered the elderly, women, and children, sparing no one. After returning, Avag Ghazaryan left Turkey and moved to Habeghyan, after which we lost his trace.

My father used to say that during the siege, the Turks approached our positions in the evening and often talked to us. They reminded us that the French betrayed us, deceived us, gave us 1 box of bullets, while they gave 7 boxes to them.

In the evenings, my father recounted that they came from about 50 meters away behind a rock and shot at us, although we had no casualties, but there were injuries. One day they decided to put an end to these uninvited guests. It was decided to place explosives and blow up the Turks' hideout. In those days, it was difficult to purchase metal items. Instead, they hid stove pipes, stones, pieces of iron with explosives behind the rock, and when Turks gathered and began firing, Armenians pulled the cord and blew up the hideout.

After these events, the Turks never appeared there again and often were cautious upon seeing a cord. The days of Hajin's fall were approaching, felt in October. The Kemalists had placed Austrian long-range cannons far from the city and easily bombarded it.

At the beginning of the siege, the Turkish cannon made only small demolitions, which did not scare the Hajin residents, but the large Austrian cannons demolished half of St. Hakob Monastery with the first strike. It caused a kind of panic among Hajin residents, and it was decided to leave the city, break through the siege, and pass under French protection in Adana. When and how that breakthrough would happen, no one knew; the order had to come from the center.

My father always performed his duty in the positions but kept repeating to his family that in case of escape, he would definitely come and take them. One evening, while my father was in position, his brother Simon came and announced that they were breaking through the front line and to leave his position. My father hurried home intending to take his family with him, but when he got home, he saw no one; they had joined the mob unable to escape and were slaughtered by the regular Turkish troops. Only those 400 armed men under the command of Aram Kaytsak (Theresa) managed to escape and broke through the siege to Adana. Here, my father, left alone and knowing the area well, managed to leave, travel a few kilometers, and hide among the bushes until the next dawn. From here began my father's odyssey.

Adana city was quite far from Hajin, about 140-150 km away, and my father had to travel this long road at night to avoid falling into Turkish hands and hide during the day among the bushes, tall grass, or in the woods. The issue was not only walking but also feeding; how and with what. My father always held his rifle and never let it go until he reached Adana. Initially, he managed with a small supply he had: a piece of ham, bread, cheese, sugar, which lasted only three days. In the following days, he fed on berries, roots, and herbs. My father recounted hearing a strong rustling in the tall grass while hiding and waited with his gun ready to see what would happen. After a while, it turned out to be a turtle, to my father's great joy. At nightfall, he made a fire, roasted, and ate the turtle and continued his way.

One day, just before dawn, he hid under a bush and realized he was near a village. In the evening, a Turkish woman was looking for her donkey, heading toward the field. My father sensed the impending danger because the woman was walking directly in his direction; he kept his rifle ready in case she came too close, he would have to shoot. At that time, Turkish villagers were always armed, and they would not miss the opportunity to kill a 'Gavur' (Armenian). Unexpectedly, someone from the village called the Turkish woman, saying the donkey was there. My father breathed a sigh of relief and moved away from that 'hospitable' place after nightfall. Late autumn rains were heavy, and once, while crossing a river, he nearly drowned, but somehow managed to save himself. At that time, he found 2-3 Hajin residents who were also headed to Adana, and in the last days, they approached the city after walking for 40 days.

My father reached Adana skeletal and frail, where he met his brothers Simon, who had come with Aram Kaytsak's group, and his younger brother Ruben, who was in Adana before the war.

Having life experience, they fed my father only with milk and light food on the first day, but it did not help, and he fell sick with diarrhea.

My father was immediately taken to the American hospital. The doctors predicted that if he lived until morning, he would recover, and that’s what happened. My father recuperated and started working. When the French troops withdrew from Cilicia, meaning, when the French left Cilicia and handed it over to the Turks, Armenians left Turkey permanently, moving first to Greece and then to France.

My father married my mother in Greece, who herself had been exiled in summer, left with two daughters, the younger of whom fell ill and died, while the elder being covered in wounds, my mother decided to wash the child entirely with lemon juice, after which the child healed. My father and mother married in Greece and a year later, at my mother's urging, my father moved to France, holding a contract with the "Schneider" company where he started working as a worker in Le Creusot city. Following my father's example, my uncles all moved to Le Creusot city and after living there for several years, decided to move to Paris in 1929 when I was 2 years old.